By Adrian Liloy

UJW Staff Writer

UJW Staff Writer Adrian Liloy was in Italy when terror struck the Boston Marathon this spring. This is his account.

VINCENZA, Italy—Deep down, I don’t feel safe.

I was only 6 years old and living in New York City on September 11, 2001, when two planes crashed into the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center.

I remember my mother picking me up from school, getting home, and turning on the news. I watched as millions of people scrambled to flee the city while the Twin Towers were enveloped in smoke and later crumbled.

I was confused. I didn’t understand what was going on.

For years after the attacks, I was traumatized. I’d have anxiety attacks every time I’d board a plane.

It’s been more than ten years, and I still don’t feel safe.

We’ve had many tragedies since then, and the most recent was the April 15 bombing at the finish line of the Boston Marathon.

Struggling with jet lag, I was fighting to fall asleep at the Key Hotel in Vicenza, Italy, when bombers struck.

I was on a trip with my mother and my stepfather, who were already asleep, until my mother’s cellphone began blowing up with breaking news notifications from American news outlets around 1 a.m. The constant, loud pings woke my mother up. She checked the messages and the very next moment, let out a loud gasp that startled me out of my haze.

My mother’s emails delivered horrifying news: the marathon had been bombed and no one knew yet who was responsible.

Immediately, she turned on the news while explaining to me what had happened.

While trying to comprehend the atrocity, an overwhelming sense of sadness came over me. My mind started flipping back through a long string of unfortunate events, such as the Newtown school shooting, the Aurora movie theatre massacre, and the Tucson shooting of former Rep. Gabrielle Giffords and 18 others, among other tragedies.

This new norm for America has left many dead or severely injured and has created a sense of paranoia and uncertainty for everyone. Now, I believe anything could happen at any moment.

As I watched news developments unfold, I wondered: What is different here? Why don’t we hear about all of these unfortunate events in Italy?

I sought out English-speaking Europeans to seek their insight.

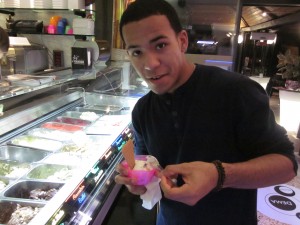

A few days after the bombing, my mother and I walked into a gelato shop and met a worker who spoke some English. I asked if she had heard about the Boston Bombing and what she thought about it.

“I think the government needs to be more careful [and] pay more attention to people who can be a threat.” said 19 year-old Natalie Martucci, from Vicenza, Italy.

In the days and weeks following the bombings, our attention turned to how the suspected bombers could plan this attack undetected. News reports later found Russian officials told the U.S. in 2011 that the Boston suspects could potentially be a threat, labeling them as radicals.

Is paying careful attention to those who pose a threat to the U.S. a simple solution that is not taken as seriously as it should be?

Had the U.S. government done this, the alleged bombers may not have been able to devise and execute the plan they did, costing three people their lives and leaving more than 260 people with serious injuries.

These were the thoughts running through my mind as I left the shop.

I looked around as I stepped out into the sunlight. I saw people riding their bicycles, couples holding hands, groups of friends sharing laughs together. Many of these people were also enjoying a nice scoop of gelato.

I then thought: How nice it would be to live in a place where the biggest worry is which flavor of gelato one should get.

The following day, as my family and I were checking out of our hotel, I noticed the desk clerk spoke some English, so I asked him what he thought about the Boston bombing.

“It’s [not] good.” said 42 year-old Davide Castello, from Vicenza, Italy. “He [needs] the death penalty because [the] other criminals will know that [the consequences are] real.” Castello said, referring to the living suspect, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev.

Castello made an interesting point, alluding to the very real—and likely inevitable—possibility that there will be other criminals who will act just as violently, if not more so, as Tsarnaev allegedly did.

Depending on what Tsarnaev’s punishment is, potential criminals may think twice before committing these heinous crimes.

As the plane took off to take us home, I took in a large, beautiful view of Italy one last time. But all that was on my mind was America and a hope it would reflect the peace I experienced in Italy.

I can’t wait until the exhaustively long list of tragedies in the U.S. come to an end once and for all.